In my previous post I discussed the "three-chord trick", and the importance of the I, IV and V chords. The use of these chords in popular music has its roots in the blues, and the best way to really see how they work together is to examine some common blues progressions.

In my previous post I discussed the "three-chord trick", and the importance of the I, IV and V chords. The use of these chords in popular music has its roots in the blues, and the best way to really see how they work together is to examine some common blues progressions.These progressions, and variations of them, continue to be used today, not only in the blues, but also in rock, country, and even (with some enhancements) in jazz. Understanding them, and how to use them as the basis for creating new music, will benefit any songwriter.

12-Bar Blues

The most common I-IV-V progression is the 12-bar blues progression, which, as the name suggests, is 12 bars (or measures) long. It's been used on thousands of songs, and you'll almost certainly recognize the sound of it the first time you play it through (these examples use major chords, but 7th chords, 9th chords and other variations can also be used to create an edgier, more bluesy sound):

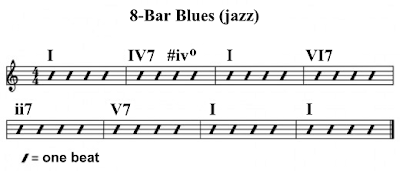

8-Bar, 16-Bar and 24-Bar Blues

The progression is often seen in a 24-bar variation, where the duration of each chord is doubled, while a common 16-bar variation repeats measures 9 and 10 three times, as follows:

Turnarounds

The simplest version of a turnaround is to simply go to the V chord in the last measure, but they can get far more sophisticated than that, especially in jazz-influenced music. To the right are some turnaround examples, which would occur in measures 11 and 12 of a 12-bar progression (or the last two measures of any progression, regardless of length).

The turnaround may also contain a short instrumental phrase, riff, or "hook", which is repeated at the end of each section. Because turnarounds are designed to lead into the next section, they are also often used as intros, leading into the first verse, or as endings, leading into the final chord.

Jazz-Blues Progressions

Blues progressions can be "jazzed-up", or made a bit more sophisticated, with some simple chord substitutions. A 12-bar "jazz-blues" progression might look like this:

Minor Blues

The blues can also be played in minor keys. In a minor key, the I and IV chord are played as minor chords (i and iv), while the V chord remains a major chord. B.B King's The Thrill is Gone is a well-known example of blues in a minor key. It uses the following progression:

The variation seen in measures 9 and 10 of this example, where a bVI chord goes to the V chord is sometimes seen in major keys, as well.

Don't let the simplicity of these progressions fool you. Future hit songs are almost certainly being written with them right now, and will continue to be for a very long time. You can use them "as is", or you can play with them. The Beatles' Day Tripper sounds like a standard 12-bar progression for the first 8 bars, at which point it then surprises the listener by going off in another direction.

Here's another songwriting tip from the Beatles: use a standard blues progression for the verses of a song, and then go in a different harmonic direction on the bridge. Can't Buy Me Love and You Can't Do That are good examples of this technique.

No comments:

Post a Comment